In 2009, two weeks into his second tour in Iraq, Army Specialist Chancellor Keesling committed suicide. His family decorated a wall in his Indiana home as a tribute to him.

Condolence cards arose during the Civil War. With no relatives around, dying soldiers were attended to by their comrades. They watched them die, dug their graves, and wrote letters to their families explaining they had died.

They placed his uniform and the flag from his burial service, leaving a space for the expected condolence letter from President Obama. But it never came. A dated policy disallowed soldiers who committed suicide from receiving them. Keesling’s father wrote President Obama and the Army chief of staff requesting the policy be changed. His son’s suicide was a result of what he was exposed to during the war, he said, not because he was weak. Earlier this month, President Obama reversed the policy. “It is simply unacceptable,” said the president, “for the United States to be sending the message to these families that somehow their loved ones’ sacrifices are less important.”

HOW TO DEAL WITH A SUICIDE

Condolence letters arose during the Civil War, a time when the deathbed was a sacred place. “Family circle closed round its loved one to offer comfort and reassurance,” says Civil War enthusiast Mark Dunkelman, in an essay on Civil War condolences titled, With a Trembling Hand and an Aching Heart. “The war irrevocably disrupted those conventions.” With no relatives around, dying soldiers were attended to by their comrades. They watched them die, dug their graves and wrote letters to their families explaining their deaths. The letters followed a formula: offer sympathy, discuss money matters, give details of the passing.

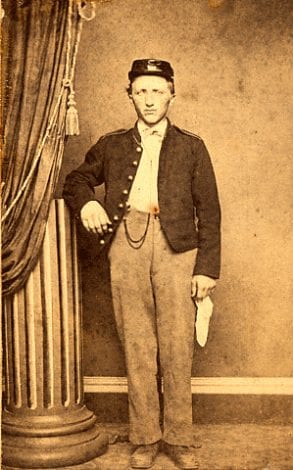

Some were more creative. The 154th New York Volunteer Infantry, a regiment from Cattaraugus and Chautauqua counties, lost 232 men in the war. The families of every single one likely received a condolence letter but only about a dozen still exist. One is to the family of 22 year old Private Edward Shults, of Ellicottville, New York. He died at the Odd-Fellow’s Hospital, in Washington, D. C. on the morning of February 15, 1863. “I thought you might be gratified to hear more of the circumstances of his sickness and death,” read the condolence letter, written by an attendant named Andrew Kemmisen. “It was painfully interesting to hear him pray and sing and shout…[we] did all we could to sooth his pathway to the grave; but we trust he had a friend that was better to him than father or mother, brother or sister.”

BURYING THE FORGOTTEN SOLDIERS OF BYGONE WARS

Over time the tradition was formalized and the condolence letter became an official note sent from the Office of the President. But letters went the other way too. After President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Jacqueline Kennedy received an estimated one and a half million condolence letters. Most were destroyed, but 15,000 made their way to the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, where they sat, untouched, for more than four decades. Recently, they were revealed to the world again, in a book written by New Hampshire historian Ellen Fitzpatrick entitled, Letters to Jackie: Condolences from a Grieving Nation.

“There were letters from dairy farmers,” said Fitzpatrick. “There were letters from children. There were letters from Republicans. There were letters from Native Americans on reservations. There were many, many letters from African Americans. Some of them were just scrolled on a little scrap of papers in pencils. Some of them were written on elegant stationary.” She divided them into three categories, letters that talked about the day of the assassination and how people responded, letters that reflected on politics, society and general views of the presidency and letters in which people tried to console Mrs. Kennedy, often reflecting upon their own experiences with grief and loss.

The youngest writer was a seven year old named Tony Davis whose letter simply said, “I’m sorry he is dead.” One of the most moving letters was also from a youngster, a 14 year old named Tommy Smith who had seen the President and his wife in Dallas just before the assassination. “Dear Mrs. Kennedy,” it began. “I know the grief you bear. I bear that same grief. I am a Dallasite. I saw you yesterday. I hope to see you again. I saw Mr. Kennedy yesterday. I’ll never see him again. I’m very disturbed because I saw him a mere 2 minutes before that fatal shot was fired. I couldn’t believe it when I heard over the radio 5 minutes later. I felt like I was in a daze. To Dallas, time has halted. Everyone is shocked and disturbed. My prayers to you, a sympathetic, prayerful, and disturbed Dallasite, Tommy Smith.”